“Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep”, while Béla Tarr wakes up the cinematic avant-garde with his filming techniques

19.03.2024

“Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep”, while Béla Tarr wakes up the cinematic avant-garde with his filming techniques

Somewhere between sleep and reality, prophecy and mysticism, the reign and downfall of the individual and the world when the Scottish crown becomes heavy, Shakespeare’s genius, reviving the world of ancient tragedy and medieval drama, stages “Macbeth” in the spirit of the English theatre of the Baroque and Restoration. Eternally relevant, Shakespeare, who easily penetrates into the essence and exposes the truth behind the theatrical mask and illusion from the earliest beginnings of cinematography, occupied an important place in film development, proving with his survival that the whole world will play forever because we are all actors (players).

Macbeth was brought to the screen first by one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century, Orson Welles, in 1948, then by the Polish-French director, the famous Roman Polanski, in 1971. Among the infamous screen adaptations of “Macbeth”, we can rightly include the one from 1982 by the Hungarian director Béla Tarr, who, with his unique innovativeness of the film technique, creates a work in the collision of the Renaissance scene and the experimental seventh art.

Director Tarr, known for his masterpieces such as The Turin Horse (2011), Damnation (1988), Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) and above all for the cult film — Satantango (1994), creates worlds of multiple perspectives, moral and ethical truth, moments of existence on the edge between life and death, taking the eternal motif of freedom of choice as a guide for his characters trapped in their own film spaces. Although “Macbeth” is one of his earliest film projects, the work in front of the camera suggestively represents the tragedy of the Elizabethan theatre through which Tarr will change the understanding of film language. Already — with this film, it was known that a new great director with a unique style would make a prominent impact on the seventh art.

Tarr’s “Macbeth”, unlike his future multi-hour films, lasts only 62 minutes and — what is even more interesting, consists of only two film frames. The first frame, which lasts about five minutes, includes the prologue and the first five scenes of Shakespeare’s play, while the second frame follows the rest of the story of Macbeth, a chronicle of one man’s disintegration. Since there are no visual frame cuts in the film, the scenes are categorized and separated from each other mostly aurally. The actors speak most of the movie in whispers, however, in critical scenes such as the murder of a dream, the coronation feast, the witch’s prophecy and on the battlefield, the voice rises to a shout, then it resembles a cry.

Ambient silence rules the film. Dialogues and monologues are also full of blood-curdling silence. This stagnant noise during the transition from one scene to another is sometimes replaced by the gallop of horses, the clanking of metal shackles, and the rapturous melody of a medieval song performed on a violin. The fiddler on the court, the royal musician (Andras Szabo), who subtly passes through the moments of greatest sadness and Macbeth’s madness, creates a contrasting atmosphere with his lively composition. The violinist does the same in another Tarr film, “The Outsider”, realized just one year earlier than “Macbeth”.

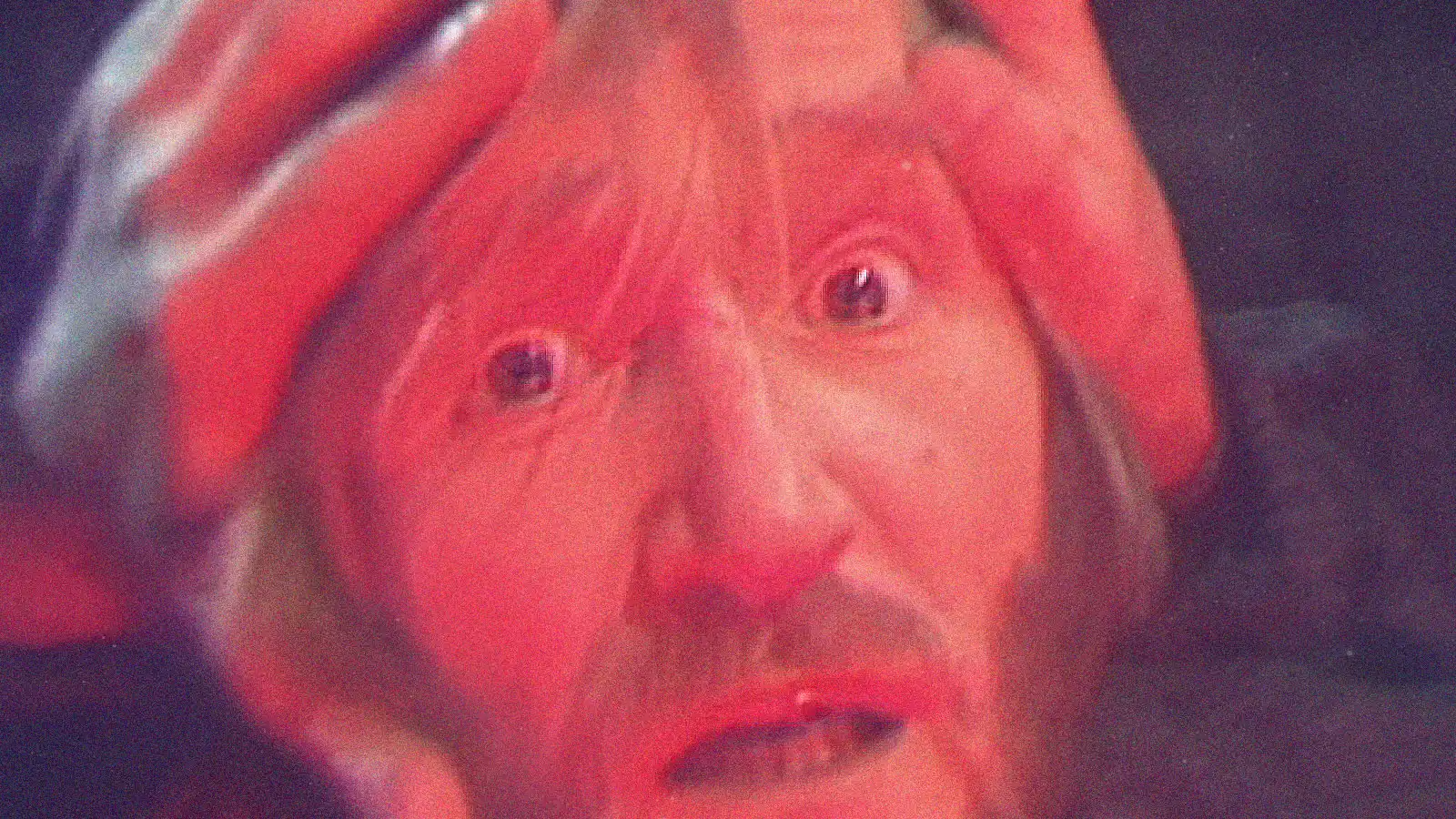

Along with the director’s films “Autumn Almanac” (1984) and “The Outsider” (1981), this work is a rare example of Tarr’s authorial corpus in colour. The entire film is painted grey and gloomy (in shades of the walls of the kingdom), except for three scenes — all three closely related to the occult. The first scene is with the witches who, at the beginning of the tragedy, predict to Macbeth that it was written for him to become king, which he will achieve by killing the old King Duncan, spurred on by his wife’s ferocious ambitions. The portraits of witches are depicted through three male characters, like storm, thunder and rain — coloured with red light. The second scene is a reunion with these supernatural beings when Macbeth is foretold to die at the hands of a man not born of a woman. The red light in this scene is complemented by the glow of the blue flame, the hottest fire. In the last occult scene, the king-killer Macbeth dies, and the whiteness of death is highlighted through the smoke of the final battle, where the king-murderer, executioner Macbeth experiences the fate of his victim.

The only female character in the film is the character of Lady Macbeth. With this procedure, the director emphasizes its importance. Her story runs parallel to Macbeth’s, just as tragic, driven by terrible ambition, madness and fear due to the crimes committed in the eyes of a lost soul. The entire film is in motion while the scenes change — the camera follows the protagonist spouses trapped in the labyrinth of the kingdom of Scotland and their own conscience, which robs them of their sleep and points to a dirty hand from human blood.

The closeup is ubiquitous and creates a link between the characters, the director and the audience. In two moments of the film, the actor’s gaze is directed directly into the camera, aiming at the audience. This happens for the first time when the “witches” firmly hold Macbeth’s eyes wide open when his body and spirit are ruled by insomnia which, no matter how hard he tries to resist, he cannot. Another time, Magduff’s gaze stalks the camera in the final segment of the film as he holds Macbeth’s severed head in his hand, marching ahead of his army to the sound of a violin. The tragedy ends.

The king is dead — long live the new king! In a cinematic representation of Tarr’s nightmare, we experienced the Shakespeare dream!

“Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

Emilija Kvočka